Richard Lutz tours the uncluttered geometry of a grey Evenlode valley

John Phillips lies in St Nicholas graveyard. He died in 1911. A few feet away lies AJ Phillips who died in 1918, aged 23. It’s a good guess that AJ was a war casualty brought home to Oddington to be buried next to his older kin. A father, grandfather, an uncle?

Between their resting places on this grey Cotswold day, snowdrops emerge… white, tough, early heralds of spring. Under a tree, there’s a hint of green daffodil shoots. All else is colourless, asleep.

St Nicholas lies above the mud that spreads from the tiny curving River Evenlode. The mud below, the grey sky above. Sodden pastures and soggy woodland surround the old church, fields are submerged, sheeptracks and paths are muddy trenches. Pastures are lakes.

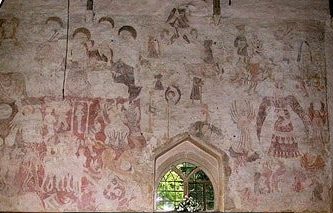

But inside St Nicholas is a giant gem: a Doom painting that covers most of the north wall. It radiates history, 700 years old, fading and fortunately never disastrously re-touched. The original hands that created this mural are of the 14thc when fearful churchgoers would look up to the wall to devils and the tormented on Judgement Day. And they’d tremble and pray.

But inside St Nicholas is a giant gem: a Doom painting that covers most of the north wall. It radiates history, 700 years old, fading and fortunately never disastrously re-touched. The original hands that created this mural are of the 14thc when fearful churchgoers would look up to the wall to devils and the tormented on Judgement Day. And they’d tremble and pray.

This vast masterpiece – it’s thirty feet long – depicts the descent into hell. The dead rise, are tortured by devils. There are four men ready to be boiled in a pot. A body hangs from a scaffold. They’re all being being eyed up by demons dressed in ludicrous striped uniforms resembling – for all the world – jailbirds in a comedy.

Above this mural of mayhem sits Christ and his acolytes, unmoved by the hell below.

The colours are faint. They’re being hidden by the centuries. But you can just about make out the deep reds and yellows for what was once, a long time ago, a frightening reality for the illiterate and the innocents of old Oddington village.

We sludge through the mud. The fields are a mess of water and muck. The sky is a solid grey. There isn’t a glimmer of winter sun.

But grey does have its variations, wispy, leaden, drab, whipped by rain, even sometimes glaring. Oliver Sacks, the late neurologist, wrote about a painter who lost his sense of colour late in life. His world turned black, white and grey. Colour, said Sacks, was ‘a historical fact…not something he could access’.

The Strange Gift…

The artist, referred to as Jonathan I, learned about grey. He found gradations in it. After a while, he found, colour got in the way of seeing the world. Sacks writes: ‘He has come to feel that his vision has become highly refined, privileged, that he sees a world of pure form, uncluttered by colour’.

Jonathan even painted a room completely grey along with its furnishings. He says, according to Sacks, that he has a strange gift, one that has ushers him “into a new state of sensibility”.

Dr Sacks points to another case. Frances Futterman was born colourblind. She wrote that she cannot define greyness. That is just her world. ‘I would also be willing to bet that if we (the colour blind) were tested along with normals (sic), in low level lighting, we would be able to detect far more shades of grey. The world I see has just so much more richness and variety than black and white photos or tv shows’.

‘My vision,’ she comments, ‘is a lot richer than normals can imagine’.

We follow fields south and slide through the mud and ultimately gain higher ground with solid earth. The roll and pitch of the land take on the artist’s geometric perspective. Because of the greyness, the Cotswolds terrain becomes long slanted pasturelands, steep lines of little valleys and strips of woodland that border the geometric fields. House nestle next to each other as we approach hamlets. Black roads wiggle through the ripple of the land. There is little colour – only outlines and shapes.

We head for Bledington where this grey sky blankets the honey coloured limestone buildings. Its church, St Leonards, is bone white inside. The north wall has narrow windows filled with fifteenth century glass. Some of the collection is re-assembled from broken fragments and, as above, some are complete.

We head for Bledington where this grey sky blankets the honey coloured limestone buildings. Its church, St Leonards, is bone white inside. The north wall has narrow windows filled with fifteenth century glass. Some of the collection is re-assembled from broken fragments and, as above, some are complete.

Reds, yellows and the deepest blues allow the poor grey light from outside to wash the nave. The coloured windows cast faint shades onto the white nave. But it’s colour, not radiant, not vivid but nevertheless thrown from the sky. This lightly coloured church is barely touched by the reds and blues, just like the fading giant mural three miles away, just like the white of the snowdrops and the green of the daffodil shoots in nearby Oddington in this winter geometry of the Cotwolds.

Reds, yellows and the deepest blues allow the poor grey light from outside to wash the nave. The coloured windows cast faint shades onto the white nave. But it’s colour, not radiant, not vivid but nevertheless thrown from the sky. This lightly coloured church is barely touched by the reds and blues, just like the fading giant mural three miles away, just like the white of the snowdrops and the green of the daffodil shoots in nearby Oddington in this winter geometry of the Cotwolds.

Maybe Mrs Futterman would have liked it. After all, she wrote to Dr Sacks: ‘I am frequently overwhelmed by the beauty of the natural world’.

I have walked that area but never explored the churches – perhaps it was not raining at the time!

…evocative….

A winter’s day and the inside of churches, always interesting. Have you read John Betjemin’s great poem Sunday Morning at Kings College Cambridge ?

I am in Ecuador and saw a huge and nightmare-engendering mural in Quito’s biggest goldest cathedral. Hell in ways I could never have conjured up, souls in process of eternal torture.

I am reading Paul Theroux’s “The Tao of Travel”, I commend at least Chapter 13: ” It is Solved by Walking”.