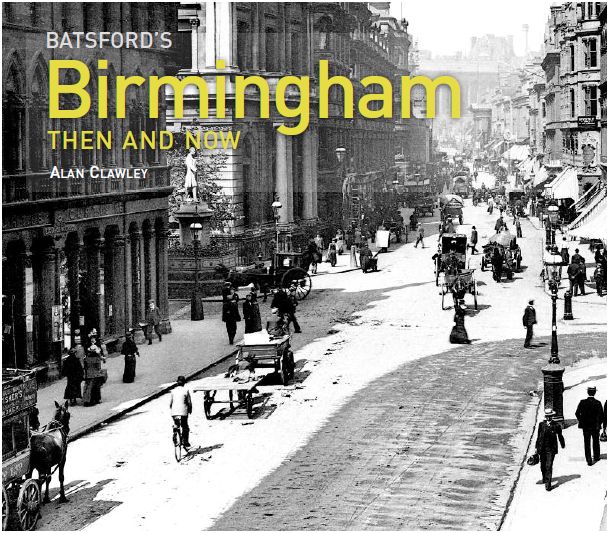

Alan Clawley has published a book in a popular series.

The Birmingham version of a best-selling series entitled ‘Then and Now’, has just been published by Batsford. When I was asked last year if I would be the author, I was sent the versions for Liverpool, Cambridge and New York as examples. Birmingham’s traditional rival, Manchester was still a work-in-progress at the time

The format of the series is to choose a set of old photos, work out where the photographer stood to take them, and take the photo again from the same viewpoint. In a city such as Cambridge, which has hardly changed for a hundred years, it was inevitable that the main differences between then and now were clothes, cars and bicycles. New York on the other hand is so big and has such a strong identity that it can shrug off changes that would overwhelm smaller cities. Liverpool is most like Birmingham, but not so big. Much attention is understandably focussed on the Pier Head, but unlike New York, big changes here can have a drastic impact on the city and even put a World Heritage status in jeopardy.

Birmingham is of course famous for changing large parts of its environment every few decades. In streets like Steelhouse Lane matching the views called for serious detective work whilst the series of Bull Ring shopping centres leave a puzzle suitable for a team of industrial archaeologists to unravel.

This is what makes Birmingham fascinating but also depressing to lovers of architecture. In particular, the destruction of the Grammar School in New Street, designed by Barry and Pugin – the team that gave us the Houses of Parliament – seems shocking now, especially when we see the bland building that replaced it.

The city fathers appear to me have had difficulty reconciling progress with respect for the past. Each generation comes to regret the loss of a fine and much-loved building destroyed by the previous generation. More respect is shown for what has been lost than for what still exists. It is as if the planners console themselves with the thought that the loss, like that of an old person who reaches a certain age, was sad but inevitable. And so, the pattern is repeated as if it is a law of nature. But it’s no consolation to hear expressions of regret after the event.

The city fathers appear to me have had difficulty reconciling progress with respect for the past. Each generation comes to regret the loss of a fine and much-loved building destroyed by the previous generation. More respect is shown for what has been lost than for what still exists. It is as if the planners console themselves with the thought that the loss, like that of an old person who reaches a certain age, was sad but inevitable. And so, the pattern is repeated as if it is a law of nature. But it’s no consolation to hear expressions of regret after the event.

Buy Alan’s book on Amazon here