The second weekend of the Gent Jazz Festival broadens its scope to funk, reggae and rock’n’roll. Martin Longley jumps, slumps and pumps…

Gent Jazz Festival

Gent, Belgium

As is its traditional way, the Gentfest pauses for a few days, then switches orientation towards jazz peripherals. We’re not talking a complete rock-pop coup, but rather an informed selection of acts who are likely to appeal to jazz-orientated beings. These might be angled towards rock or electronica, reggae or Latin, funk or global sounds. Even though phase one was mostly very well attended, the second week jolts up to an even higher level of ticket sales, with queues stretching far out into the distance. Three out of the four evenings involved having all seats removed, the marquee given awning extensions that allowed even more folks into the absolutely crammed undercover space. This was great for commercial success, but frequently created a situation where achieving anything like a close proximity to the stage would involve camping out for several hours in advance. Often, a sacrifice would have to be made where a viewer would settle for the general ambiance rather than full immersion in sound and vision. This was, once again, where the handy stage-side projections were an asset, even though there’s always an element of the ridiculous involved when watching a live performance on a real-time screen.

There were just two acts on the first night of the second week, presumably because Antony & The Johnsons were set to play an extended set. Actually, there didn’t appear to be a Johnson in sight, as Mister Hegarty was backed by The Metropole Orchestra, repeating a lavish stage concept that was previously seen at New York’s Radio City Hall. Local Belgian singer and violinist Liesa Van Der Aa opened up the evening, mostly playing solo with the aid of massed foot-pedals. She was eventually joined by a band, her chief influence seeming to be England’s P.J. Harvey, although metamorphosed into a melodramatic caricature. Van Der Aa didn’t have much of her own personal style to offer, her songs bearing the brand of lazy pastiche. She didn’t really play much violin, and when she did it was to emphasise her picking-and-strumming, would-be ukulele techniques.

Antony Hegarty must surely fantasise about being an opera diva, clad in his voluminous black gown, face daubed chalk-white, ringlets cascading into the night. The old songs just might be the best songs, as his current repertoire lacks the essential quality of melodic resonance, particularly when his voice was so centrally framed and highlighted by the Dutch orchestra. His stage patter was amusing, surreal and heavily anecdotal (when it was audible), giving the feel of an intimate chamber recital. Unfortunately this didn’t project too well for many of the assembled thousands. Also, the Metropole was quite possibly present in reduced form, their arrangements being somewhat minimalist even given the available resources. Surely more could have been made of their physical presence? Hegarty must have requested that the live video images be static, and this was a touch of the uncompromising that should be respected. However, such an absence of camera movement meant that the far reaches of the crowd weren’t helped out with their visual handicap. Theoretical intimacy became grand spectacle from afar.

The Belgian quartet Amatorski opened up the next evening, with their sparse electro-ambient pop. Their name is apparently the Polish word for ‘amateurish’, doubtless something of an in-joke for the band. Whilst being hesitantly simple in their delivery, the players were still in command of their stripped intentions. Faint-voiced Inne Eysermans conveys a deliberate waif-image, at home in her cardigan, crafting skeletal tune-lines on her keyboard and laptop, deep in her bedroom studio. The Amatorski antecedents must surely be combos such as Pram and Stereolab, or even the Young Marble Giants.

Tindersticks maintained the mood of contemplative introspection, probing the finer nuances of what might still be called rock music. This English group have always held a membership with the select club of songsmiths who are concerned with contained dynamics, limited curves of peaking intensity and a dramatic (or even melodramatic) sense of romanticised angst. Or romance as windswept pain. Their closest cousin is Nick Cave. Singer Stuart A. Staples is so immersed in emotional intensity that, with his deliberately retro Scandinavian cabaret-crooner image, he passes dangerously close to the borders of parody. But this is a form of parody that’s laughing grimly with itself. When the band gathered their forces into strategically placed outbreaks of rocking potency, these power surges were all the more profound, surrounded as they were by a shimmering motion on the highway to terminal melancholy. This is a state that Tindersticks embrace with true love.

One of the festival’s absolute highlights was the Jamaican Legends set featuring the reggae supergroup of Sly & Robbie (Sly Dunbar on drums, Robbie Shakespeare playing the bass), Ernest Ranglin (a reggae guitar forefather) and Tyrone Downey (keyboardist member of Bob Marley & The Wailers). Sly & Robbie have straddled the styles over the decades, from classic dub through electro-dancehall and well beyond the borders of reggae, working as producers and players in rock, pop and experimental zones. Stand-out projects have included work with Grace Jones, Mick Jagger and Bob Dylan. Ranglin started out with early ska and ended up creating his own form of jazz-reggae, in a similar fashion to that chosen by pianist Monty Alexander, who was originally booked as the leader of this project. In a way, it was fortuitous that Alexander was forced to cancel, as this meant that we could witness a rarer appearance by Downie, making this a more direct Jamaican music summation. Sly & Robbie have a very reclined motion, the drummer (sporting a red hardhat) perfectly measured in his minimalistic emphasis of crucial beats, diligently dissecting the essence of rolling motion, the bassist trundling loosely, with an oozing wobble. Even when Ranglin wasn’t delivering an effervescent solo, he’d stalk the rear of the stage, locking eyes with Dunbar as he chopped out a tight rhythm part. Downey was usually the audience communicator, delivering vocals on the now-predictable inclusion of Marley’s “Redemption Song”. For the encore, though, Shakespeare took another overplayed song, Dawn Penn’s “You Don’t Love Me (No, No, No)”, turning it into an almost chilling version, partially a capella in its delivery, decelerated and mournful.

Another return visit from 2009 was made by Rodrigo y Gabriela, this time with their expanded C.U.B.A. line-up in tow. The Mexican duo have followed their instinct for sonic expansion to its ultimate conclusion. Their own distinctive breed of acoustic magnification has now been augmented by a full crew of sympathetic players. They still chose to present a twosome acoustic guitar mid-section, but this made the onstage return of the band all the more impressive. There are now drums, bass, piano (Alex Wilson, an experienced Latin jazz bandleader himself) , trumpet and saxophone, retaining the old style of material but inflating it with further points of dynamic interest, enhancing the core duo drive. Even so, this touring version of the band is about half the size of the Cuban posse that recorded the relevant Area 52 album (PIAS, 2012). Gabriela still features ample finger-percussion enhancements, whilst Rodrigo took up his electric axe for a showcase soloing surge. Despite the sense that many of their moves might now be too entrenched due to over-frequent festival appearances, Rodrigo y Gabriela still delivered a stirring show. The set seemed longer than most, possibly due to its overabundance of crowd-baiting routines.

The closing day lunged towards The Funk. Well, the Belgian openers Stuff could partly enter that genre compartment, although their mode of syncopation was more of a jazz funk style that was simultaneously 1970s/80s retro, as well as having those moves filtered through a modern times mind. The presence of Andrew Claes and his ewi (electronic wind instrument) was the most problematic. He made no attempt to advance its available sounds, or offer any fresh licks that might make this horn less irritating. In the days of digital trigger-fingers, his chosen instrument was antiquated, but without the novelty, quaintness, kitchiness or sheer reverse-coolness of many other alternative old-time weapons. Their turntablist Mixmonster Menno tended to slap large chunks of pre-existing audio onto the soundscape, rather than using vinyl source material as a springboard for his own sonic invention. The band’s stated influences and beat-sources are completely current (Flying Lotus, Hudson Mohawke, Dorian Concept, etc.), but this wasn’t apparent when listening to this performance.

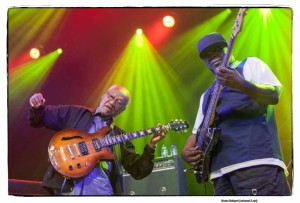

The real funkin’ commenced soon afterwards, and it couldn’t have been more real than having the resplendent vision of bassman Larry Graham. Beginning his career with Sly & The Family Stone, Graham is the closest we can get to the music’s core. Along with James Brown, Stone and his crew were the original architects of funk itself. Graham Central Station remain in peak form, delivering a festival-scale set, but without seeming forced in their entertainment routines. Despite revelling in the ultimate flamboyance, Graham and gang were completely convincing as musicians simply and viscerally getting down with their throbbing and thrunking thang. The band appeared from the rear of the tent, emulating a New Orleans parade band, but in the funky fashion. Ashling Cole’s lead vocals were a crucial part of the thrusting assault, her powerful, range-striding voice aided by a naturally outgoing communication with the crowd. Graham danced across his effects pedals, suddenly slamming on a distortion sound for a brief blow-out, then slapping right back into an obsidian tar-stretch thickness. At one point, he descended into the audience, and could be seen gliding through the masses with supreme smoothness and balance. It turned out that he was being trundled along on an oiled-wheel trolley, pouring out an excessive fuzz bass solo as he perambulated in style. At the end, the Sly Stone greatest hits climax coincided with a massed stage invasion by the invited throng, Graham clearly enjoying an exchange programme with audience/performer roles. Along with Jamaican Legends, this was the second week’s triumphant performance.

This was a most unfortunate turn of events for D’Angelo, who was the ostensible headliner. It was no help that this singer, guitarist and keyboard player’s slinky songs feature funk as a significant part of their make-up. D’Angelo has recently emerged from a self-imposed ‘early retirement’, so there was the sense that he had something to prove, to re-establish his prominence. If he hadn’t been immediately preceded by Graham Central Station, D’Angelo’s set would have fared much better. As it happened, some slow building was required to excite the now admittedly further enlarged crowd. The gradual stoking was probably a deliberate tactic, the stage loaded with multiple guitarists, all steaming along to massed groves, dedicated to the cumulative strut. It was very noticeable that D’Angelo has none of the casual naturalness and humour of, let’s say, Prince, inflated as he is by a serious attention to being the unsmiling non-deflatable seducer of all the ladies in the house. Compared to Graham’s natural confidence this seemed somehow laughable, the funk pumped full of artificial testosterone substitutes. Finally, the songs sufficed, as the slick assemblage layered up dense plates of alternating soul, rock, funk and hip hop elements. It took some time, but the set ended up being something of a sprawling leviathan anyway. One one level, the ongoing pulse-motion of the band had to be admired, but their wide-ranging musical forms were all being filtered through a mainstream R&B sensibility.

Larry Graham’s Grand Central Station play at Clapham Grand, London, on Monday the 10th of September 2012…