Martin Longley just can’t get enough of Belgium! This time he returns to review the Antwerpian Jazz Middelheim festival weekender…

Jazz Middelheim 2012

Park Den Brandt

Antwerp

Belgium

The Jazz Middelheim festival is a weekender that hasn’t relinquished its fondness for adventure over the last four decades. Nuzzling up against stellar bookings are acts, Belgian and otherwise, who seek to jolt the expectations of many audience members. The entertaining middle way is subverted by the sideways thrust of jazz extremity. This too can often be entertaining. 2012 is the fifth year that Bertrand Flamang has been in charge of organisation and programming. He’s already known for over a decade’s sterling work running the nearby Gent Jazz Festival, and has rapidly established a house style at Jazz Middelheim. There’s a similar format, in terms of stylistic contrasts, timing structure, food vendors and Belgian beer range. The main practical difference to the Gentfest is that the marquee stage is more integrated with the landscape of its park setting, all of the bars, stalls and food outlets ranged in a roughly circular fashion around the festival’s musical heart. It’s possible to sprawl on the lawn and still enjoy a (distant) view of the performers, should such a casual engagement be desired. If choosing to sit up close, an early arrival is advised, as attendance was gratifyingly swollen, even in these hard times. Unlike the previous month’s Gentfest, Middelheim enjoyed a constantly sweltering heatwave, prime conditions for enjoying the park environs. The official festival liquid might well have been rivuleting sweat rather than rushing rain water, but who could complain following months of Northern European drabness?

The day before Middelheim began, its opening night headliner suddenly pulled out. Ornette Coleman had suddenly been taken ill, and panic doubtless spread amongst the organisers. At very short notice, alto saxophonist John Zorn stepped in, continuing his ongoing relationship with this festival. His swiftly drafted cohorts were bassist Bill Laswell and drummer Milford Graves, forming an immediately tantalising trio. Just before their set, there had already been an orgy of guitaring, headed up by Larry Coryell and Philip Catherine. This had opened with the American Coryell hosting the German acoustic guitar threesome of Helmut Kagerer, Paulo Morello and Andreas Dombert. Coryell was left alone to improvise a captivating acoustic shimmer around Ravel’s “Bolero”. He was then joined by the Belgian Catherine for a duo section, the latter providing a harder contrast, his amplified sound very slightly distorted, with a grittier edge. The pair weren’t sitting at extreme corners, but there was just enough difference to set up a gentle tension. Catherine emitted a greater, fuller resonance, flooding outwards in every direction. Coryell was more contained, more focused on the miniature detail. The twosome delighted in fleet dual runs down complicated pathways, engaging in a convoluted chase. They radiated a sheer smiling ecstasy when playing together, peaking with “Nuages”. Then, the Germans returned for an encore, the full quintet playing an arrangement of “Tadd’s Delight” (by pianist Tadd Dameron). One encore turned into two, as each guitarist soloed in a wave, from left to right.

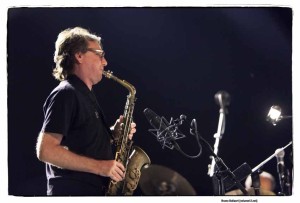

John Zorn, Bill Laswell and Milford Graves have sporadically worked together as a trio. One New York date in 2008 had Laswell drop out to be replaced by Lou Reed, ultimately resulting in all four of them subsequently playing together. Guitarist Marc Ribot is another sometime member of this loose formation. As their set evolved, there was the hope that Zorn might be in the mood for invoking the presence of the absent Ornette, as with his storming Spy Vs Spy album (Elektra/Musician, 1989). Gradually, Zorn’s alto took on the Coleman hue, the tone, the careenings, the crying. Yes, that was “Mob Job”, given the thrash condensing treatment on Spy Vs Spy, and originally heard on Song X (Geffen, 1986), Ornette’s album with Pat Metheny. Zorn and Laswell found a duo moment, which was followed by Graves demonstrating his one-man-band skills, embarking on an Afro-Latin-Caribbean journey, vocalising and utilising the percussive details of his drumkit. Most of the time he’d been in abstract-tumbling free jazz freefall mode, but this sequence highlighted his Afro-storytelling side, even if the tale was non-narrative in nature. It was still a story in sound. After a spell, Zorn and Laswell joined in, the bassman effortlessly sliding into the diaspora downbeat. It was amusing to hear Zorn in spuming Cuban/Haitian/Brazilian bobbing motion, although he soon derailed the tune towards a serrated conclusion. When Ornette’s “Lonely Woman” entered, shivers coursed down all our bodily extensions. It began as a chillingly soulful cry, before Zorn took it to the outer limits, still not relinquishing the tune’s levitating qualities. Zorn (sporting a Stone t-shirt, advertising his own NYC venue) made bluesy, bombarding streaks, spit puffballs hitting the blooming stagelight aureoles. Laswell’s range was mostly mid-, as he concentrated on chordal wedges, filling out the space with his stack-heeled pedals. Perhaps he could have offered some deeper, more defined, single-note sub-rumbles. There was oft-times an indistinct quality to his sound. Many moods were traversed, from raging bullishness to keening lyricism. It was impossible not to notice the empty chair to stage-left, guitar propped against amplifier. Were Ribot or even Reed in town? Surely, Coryell wouldn’t be joining the trio? Well, yes, it was indeed Coryell as the set-climaxing guest star: a most unusual combination. All the guitarist had to do was invoke his old electric behemoth Power Trio persona, razoring out circular ascendant figures in Sonny Sharrock fashion. As a visitor, he had to be prompted by Zorn before unleashing a fully aroused solo, but once started, Coryell’s rugged outpourings mingled easily with the torrid miasma of the core threesome. Zorn also gave subtle prompts to the other two members, but that was part of his own improvising strategy, and surely allowed in a style-bounding set that sounded equally divided between themes and spontaneity.

The following afternoon, Ornette was still being considered as sometime sideman Greg Cohen name-checked the absent altoman. He also played a Zorn Masada tune, along with three of his students from the local Artesis Conservatorium. Cohen mostly gave them his own pieces to play, but also slipped in Nelson Riddle’s “Route 66” (his television series theme, not the more familiar Bobby Troup ditty). Cohen gave his able pupils plenty of room to roam, but his own bass was perpetually and meatily in the middle. There were even a few more abstract stretches, with exchanges between piano and drums, bow and chains on the latter.

It’s always advisable to keep the portals open at jazz festivals, but when the dapper Dutch trumpeter Eric Vloeimans presented his project with the Holland Baroque Society, it was hard to discern the intention. Not that a gratuitous Early Music session with refined trumpet solos and embellishments was a totally evil concept, but the end result was exceedingly polite for a jazzfest. Bach and Telemann preceded the leader’s own “Wet Feet”, which appropriately featured tiptoe-ing organ and pixie bandoneon. This wasn’t so much a fusion, as the authentic article, with a faint dusting of jazz technique. Two thirds in, there was a welcome turn towards Moorish and Gypsy stylings, and the latter-angled piece roused the audience from their concentrated trance (or slumber). Marc Constandse was an asset to the band, showing off his skills as a singer, bandoneon player and frame drum percussionist. One of the three violinists switched to harmonium, sitting on the stage-floor and singing along with Constandse. The Vloeimans tone was reminiscent of that found in the playing of the Lebanese trumpeter Ibrahim Maalouf, lightly dusted with Arabic filaments, dancing nimbly around the formalised arrangements.

Next, there was a rapid switch to duo intimacy, although the scale of the actual music was grander, more forcefully winding the audience in their guts with its playful exuberance. The Italian pianist Stefano Bollani continually surprises with whichever fresh setting he elects to present, from density to spaciousness, the dramatic to the mischievous. Partnered with the Brazilian Hamilton De Holanda, matters turned to a fun-filled manifestation of folkloric-flavoured tunes from that land, combining effervescent, speeding virtuosity with winkingly humorous antics. De Holanda plays the 10-string bandolim (the Brazilian version of the mandolin). The pair flirted with tunes penned by Tom Jobim, Hermeto Pascoal and Egberto Gismonti, rattling organic notes off at hyper-speed, in a seemingly effortless fashion, playing closely together, but not so close that they rendered each other superfluous. Bollani frequently sought refuge inside his piano, or sang along with his own rivulet phrases, coming across as the Chico Marx of Italian jazz improvisation. Without rejecting the cerebral thrust of advanced technique, the extremely empathic duo managed to concoct a lively romper room environment, their joyous, celebratory approach both entertaining and challenging. It was a wondrous thing, mostly full tilt (and fully tilted), sustaining passion, enthusiasm and energy, matched with a tinkering invention.

This festival’s annual appearance by the Belgian harmonica player Toots Thielemans has almost moved beyond mere gig-status. It’s clearly a social occasion, and this feeling was exacerbated by the celebration of his 90th birthday year. A short film was shown, partly in homage, but also partly because his set wasn’t expected to extend much beyond the 60 minute mark, even though Thielmans still appears relatively vigorous for his age, articulate performing abilities unimpaired. The festival grounds were at their fullest, with the crowd sprawling over absolutely all available space, every seat inhabited. It was almost a religious gathering. Rarely will such a large mass of punters (in their thousands) be so respectfully hushed and attentive. Thielmans was joined by his regular band, keyboardist Karel Boehlee, bassman Bard De Nolf and drummer Hans Van Oosterhout. Toots is an institution. Nothing went amiss in the songbook, everything was perfectly sculpted to please, like calming dinner music: appealing to all. It became easy to drift out and off, but this was a form of ambient music, at least when heard from outside the marquee’s heart. Thielemans was looking just a touch more fragile since I last saw him at 2010’s Middelheim, but his spirit is still willing, and he still delivered two encores, as well as a slow sending-off parade as the band left the stage, Toots seemingly waving and smiling at every single member of the massed encampment.

MixTuur was just as the name suggests, punning on its leader’s moniker, as accordionist Tuur Florizoone wove African textures into a large-scale jazz tapestry. This was a journey back to the classic days of 1970s and 1980s Afro-jazz fusion. A similar sound palette seems less popular nowadays. There’s something about the particular interlacing of jazz and African parts that resonates back to that era. Not that the style was even remotely retro: it’s something indefinable about the approach, this peculiar form of melding, where each spread of traits remains pure and uncompromising, though effortlessly aligned. The Blue Notes, those innovative South African exiles, and their subsequent combos would be the prime antecedent, although MixTuur’s music was more Congolese in nature. There was a band within a band, with the Nabindibo female vocal trio joining lead singer Tutu Puoane. One of the threesome had a particularly distinctive, high-ranged ululation, compatibly worked into the general streamlining. The balafon player Aly Keita was a spirited part of the core Afro-contingent, whilst tuba and trombone specialist Michel Massot was the most familiar member to the beyond-Belgium world. Massot worked closely with trumpeter Laurent Blondiau, making something of an odd couple horn section. Sometimes they’d both be using mutes, trumpet and trombone burbling in a symbiotic dialogue. When Massot hoisted his tuba, the effect was even more remarkable. Although there was no lack of solo spotlighting, the prevailing thrust of MixTuur was in the strength of their rousing ensemble passages, full of depth and balance. They were extremely well-rehearsed, and it turned out that Middelheim was the peak of a very active gigging summer for this band.

Singer Zara McFarlane is a rising vocal star on the UK scene. She’s signed to Brownswood Recordings, the label that’s operated by DJ Gilles Peterson. Presumably an unknown quantity in Belgium, Londoner McFarlane retained her fresh-faced inexperience, yet steadily constructed a performance that increased its effectiveness in a very measured, professional manner. Clearly more accustomed to playing in smaller clubs, she soon came to inhabit this much larger platform with some measure of assurance. She mixed the standards “Night And Day” and “On Green Dolphin Street” (with words) with a clutch of her originals, including “More Than Mine”, which takes a quite conventional post-break up, wounded soul sentiment, but splicing it with a mixture of bitterness and transcendence. Revolving around a compulsively repeated tune-spine figure from pianist/composer Peter Edwards, the tune sees McFarlane construct a desolate scenario that ends up with some kind of triumph. She also dropped in a re-arranged Harry Whittaker tune, transforming and re-titling the pianist’s work. Towards the set’s conclusion, McFarlane delivered a radically jazzed-down interpretation of “Police And Thieves”, the old Junior Murvin reggae song from 1976. The tenor saxophonist Binker Golding played a crucial part in the set’s intensification, repeatedly shaping a white hot core within each tune. He’s an as-yet unsung hero of the horn, but we’ll be eagerly on the lookout for his presence in the near future. Golding’s toughness had an abrasive pushiness, every solo crackling with energy, often streaked with the blues. At the beginning of McFarlane’s set, there was nothing massively remarkable happening, as she opened with a conventional jazz mellowness. Yet another young singer continuing the line of mainstream standard song, we thought. But then she gradually began to reveal more substance, not least with the spellbinding “More Than Mine”. McFarlane might need to learn some more advanced verbal stagecraft techniques, but as a singer she’s already developed her first wave of strength.

Paolo Conte looks like an old bloke who’s just got up to sing a song in his local bar. Except that, despite his rumple-jacketed, military-trousered, pot-bellied bearing, this Italian maverick happens to have a slickly suited band ranged across the stage behind him. They’re in the style of a 1920s dance band, quirkily arranged across the boards. There was a huge obsidian block to stage left, which turned out to be some kind of upright piano, either authentic or electric, it was hard to decide. To the rear sat three acoustic guitarists (subtly strummed electric axes were occasionally allowed). To their side was a horn section, and there was a drummer high on a podium to stage-right. Not the normal set-up. Conte frequently encouraged his soloists to stand out at a frontal microphone, although such soloing was also allowed from their accustomed stage positions. The parade moved from trumpet to violin, and a sequence of saxophones, then Conte whipped out his kazoo, on one song actually singing all of its verses through this buzzing tube. For his first number, Conte stood at the front of the stage, but then he sat at the piano to deliver most of the set, occasionally straying over to the marimba. He looked completely at home in his barroom away from home. With his wonderfully rich, deeply grainy, crumpled velvet, nicotine-encrusted voice (even if he’s a non-smoker), he could be viewed as belonging to the line of singers that include Tom Waits and Nick Cave, except that Conte, at 75, is much older and more ingrained in his career than both of those arch individualists. The same goes for any comparison with the avant tango growler Melingo, who’s also much younger, but maybe a namecheck of the adopted Argentinian tango pioneer Carlos Gardel will stick. Not that Conte’s songs are essentially tango, but that spirit is as strong as any core Italian sensibility. His landscape is almost pan-European in scope, scooping up traits from the romantic southern Mediterranean lands, as well as the far shores of South America in general. Ultimately, his compositions are without a defined home. Conte creates works that are born in their own land. The songs invoke old-time sepia jazz, and even the occasional country-style ramble, the latter arriving at the climax, with drummer Daniele Di Gregorio maintaining an almost rockabilly crash, seemingly forever. This led to a pair of show-stopping klezmer-style solos from violin and clarinet. At over 90 minutes, this was one of the festival’s longest sets, but Conte kept it careening madly for the entire duration, the consummate host of intimately personal expressivity.

A new day, another eccentric big band. Belgium’s own Flat Earth Society always display a fundamentally similar heart, but this is a gang that often favours some kind of collaborative theme, a new project to keep their over-fertile minds hyperactive. The concept for this set was to invite Dutch cellist Ernst Reijseger on board, offering him ample soloing space, whether bowing with sleek strokes or plucking his axe like a banjo on his knee, or even employing a skeletal variant model, which looks rather like a Malian n’goni. Reijseger is still most renowned for being a longtime member of the Clusone 3 with drummer Han Bennink and reedsman Michael Moore. Trumpeter Bart Maris had been running the late night avant-jam sessions during the course of the festival, and emerged from the ranks to play an arresting solo, captivating for its sonic properties, but also its visual oddity, as he was the first hornman I’ve ever seen dipping his bell into soapy fluid and blowing large bubbles as part of his routine. Almost as strange was the interlude where keyboardist Peter Vandenberghe pranced centre-stage for a dance display, including a rare instance of barefoot tap-dancing. Leader Peter Vermeersch’s between-tune announcements were doubtless suitably witty and surreal, but this non-Dutch speaking scribe wasn’t able to grasp their essence. When he speaks in English, though, his observations usually provoke a smile. All of the pieces were heavy with complex momentum, but there was always room for solo details in-between the ensemble ramrodding.

The Belgian pianist Jef Neve is also a festival regular, but this time he was presenting Sons Of The New World, his latest expanded group concept. This involved a five-piece horn contingent, beyond the piano trio core. This was another instance of a set suffering due to its placement. The FES assault had been so dynamic, unusual and exciting that Neve’s new work seemed very conventional by comparison. He’d opted for a very smooth, linear nature, the horns harmoniously burnished into a glowing unity. The presence of French horn alongside the more usual trumpet, trombone, saxophone and clarinet heightened this effect. Under normal circumstances this would have been sufficiently alluring, but following FES it became an enforced breather between the surrounding intensities of that sprawling big band and the soon-coming power trio led by Israeli bassist Avishai Cohen. The subject matter of this new suite of pieces dwells on recent tragic or transforming events, and this made it doubly frustrating that the music was so neutered. The Arab Spring, the Japanese tsunami, and the Pukkelpop festival stage-collapse all deserve sounds and delivery of a more arresting and confrontational nature.

Avishai Cohen projected the feeling that he was going to cram every last ounce of musical energy into his allotted 75 minutes of playing time. He has a new trio of youngsters now, and their extrovert characteristics were equal to their leader’s lofty levels. There were to be no diversions here. Pianist Omri Mor immediately set about establishing his presence with a series of extended solos that were like mini-compositions, undergoing their changes as a gradual, logical progression, ebbing and flowing with the dynamics of meditation and explosion, funkiness and lyricism. A Lebanese traditional tune was grabbed tightly, with Cohen commenting that music isn’t subjected to political borders, then he shifted to a Sephardic Ladino piece. Often, he utilised his voice as a closely partnered accompaniment to the bassline melodies. Mor was embraced by the audience with visible and audible enthusiasm, set to be a fast-rising star of the scene. Even though the set looked like it was close to its conclusion after an hour, Cohen proceeded to play for a further 20 minutes. Was this an extended encore, or was he just pausing to amass energy? This was a band that was making a complete effort to deliver its best possible performance.

The festival’s closing set brought everything down (or even up) to a highly concentrated plane, with the august South African pianist and composer Abdullah Ibrahim favouring a sensitively controlled interpretation. He’s something of a benevolent dictator, when keeping his mini-orchestra in check. This created a magical potency, as almost every solo was reined in to a compact length, brevity meaning profundity as the horn cycle passed quickly but smoothly. This was a rare opportunity to catch Ibrahim’s long-running Ekaya band concept. The quartet of Cleave Guyton (alto saxophone, flute), Keith Loftis (tenor saxophone), Andrae Murchsion (trombone), and Tony Kofi (baritone saxophone), were precisely poised, tasteful without being bland. It was a return to cool restraint that seemed almost quaintly nostalgic. It wasn’t laid back as in lazy and slack, it was dreamily coasting but with a tightly harnessed authority. The audience were transfixed, although the music clearly wasn’t dramatic enough for some, as there were a surprising number of early-leavers during the performance. The majority, though, remained in a hushed, captivated state. Ibrahim is an old school leader, demanding discipline from those around him: he’d formally call forth each player to take their individual bow at the front of the stage. He also purposefully walked across the stage to call a halt to the filming crew’s onstage activities, keeping the images at bay, allowing shooting only from the rear of the marquee. Psychologically, this magnified the ensemble nature of the proceedings, as the images tracked slowly along the front line, tranquillity magnified.

Avishai Cohen plays at Ronnie Scott’s Jazz Club, London, between the 15th and 17th of October 2012…

Zara McFarlane plays at the Contemporary in Nottingham on the 29th of November…