Alan Clawley’s review of the Stuart Whipps Exhibition– ‘Why Contribute to the Spread of Ugliness?’ at the Ikon Gallery until 5 February 2012

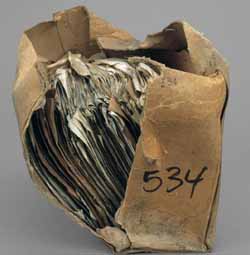

Stuart Whipps is a photographer who, in a voluntary capacity, has been looking through the archives that are hidden away in the basement of the Central Library. Over 400 boxes stashed there contain papers donated by Birmingham architect John Madin after his firm closed some years ago. Whipps’ photos are not only of some of the contents but also of the containers themselves, the deteriorating brown cardboard boxes with lids, that to half- closed eyes can take on the form of a Madin tower block, itself designed to contain armies of office workers and their paperwork.

Records of Madin’s study tour of American public libraries that Whipps found in the basement inspired him to retrace Madin’s steps some 50 years later and photograph what still existed. One interior could be mistaken for Madin’s first major work, the Engineering Employers Federation in Edgbaston.

Whipps leaves us to work out our own, not necessarily rational, answers to his question ‘Why contribute to the spread of ugliness?’ I understand that it applies mainly to the section of the show that was inspired by the exclusion of the Welsh slate quarry town Blaenau Ffestiniog from that bureaucratic ‘box’ labelled ‘Snowdonia National Park’. The slides however, focus on the countryside around the town, not the huge blue-grey tips and quarries that loom over the town itself.

It is said that local architect Clough Williams Ellis got his way on this issue but I think it more likely that the government didn’t want the planning restrictions of National Parks to limit the freedom of business to grow and develop there. The huge limestone quarries around Buxton and even the town itself – not ugly by any means – were likewise excluded from the Peak District National Park.

Williams-Ellis is best known for creating his own Italianate fantasy village of Portmeirion – of ‘The Prisoner’ fame – which, ironically, lies outside the Park, as did the proposed new seaside town of Bron-y-Mor near Tywyn, which Madin was commissioned to design and which was praised by Williams-Ellis, although never completed. One photograph in Whipps’ exhibition is a typed draft of a ‘promo’ for the Towyn scheme. Although not mentioned in the exhibition, Madin’s new holiday village at Aberdyfi was in the Park when planning permission was granted, and the obtrusive Trawsfynydd nuclear power station in the Park near Blaenau only had to be ‘beautified’ by a famous landscape architect to make it acceptable to the planners.

Although the show is officially supported by the Central Library to mark its move to the Library of Birmingham, Whipps doesn’t mention the new building, thus leaving us to consider its role as the new container of Madin’s historic archives.

The catalogue of Whipps’ thought-provoking exhibition ends with an excellent ‘Forward’ (a pun on the city’s motto?) written by award-winning novelist Catherine O’Flynn.

You buy a copy of Alan Clawley’s book ‘John Madin (20th Century Architects)’ here