Autumn means apples and orchards to Richard Lutz.

I am spending a lot of time up a big ladder these days, roaming through my three big old apple trees. Nowadays most trees are small and easily accessible, but my big ones, which provides cookers and eaters, are old and they are big, all tangled up, a maze of branches and fruit.

I always smile because way back when, I would always head for the fruit orchards for the autumn picking to make money during college. Basically I have been picking for forty years.

Orchards were all around us in the American state of Maine. It was piece work; the more you picked, the more you earned.

You showed up and were given a sticker. That was your ident. Then you were given a metal bcuket with a neckstrap. You carefully picked the apples til the container was filled and the muscles of your neck were straining.

Then you would clamber down the huge tree – which provided a lot of huge eaters called Macintoshes – and opened the canvas bottom of the container. You dropped the apples in a massive crate with your ident on it. That was your pay packet.

A supervisor would roam the orchards checking you didn’t bruise the fruit by dumping them in the big crate or that the actual crate was filled. Once checked, they would be lifted and taken to the warehouse and your crate doublechecked and its price added to your weekly pay. The apples would go into a wash and then divided into eating apples and mash for non-alcoholic cider. Where I worked, West Breeze Orchards, cider was the money maker. It was delicious.

You could do three crates per day at a maximum. But the boys who could really pick fast were the Nova Scotians. They would come down across the Canadian border, droves of them, whole families. The single guys were put up in big clean bunkhouses. Families were given small orchard cottages and these migrant workers could pick as fast as lightning.

The idea of good picking high up the trees was to slightly twist them off their dried stems. This way they weren’t bruised or dropped. Too early in the harvest and the stems would still be pliable, hard to twist. Too late and an October storm would knock the fruit to the ground. They’d be useless. You could get two apples in one hand. The Nova Scotians, straight off the hard labour of their hardscrabble farms, could do five or six with two hands. For them, there was no messing around, no idle talk, just a cigarette and a gulp of water and then back up the tree.

They would put in a good ten or twelve hour day and would land six or seve n crates. If their wives could get free from the kids, they would pick too – just as fast as the men. Their kids as young as twelve did as well. Why they weren’t at school was a big question I never learned.

To get up the tree with your metal basket they gave you a special ladder. It wasn’t a fancy metal extension job , it was a very tall rigid wooden thing with a pointed tip to spear through the branches.

I loved the job and being a bit more lithe and agile than I am now, I could get really high where the sun would shine and bounce off the giant apples at the top (with the air and light) and be illuminated by the fall sunshine. At night, I would go to sleep seeing red and green apples on long branches picked out by a sharp New England blue sky.

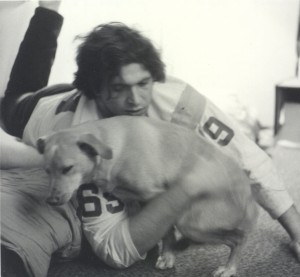

Sometimes, my friend Marshall would join me. He was a big guy, a solid 6’ 5”. He played on the defensive line at college football. He was adept with moving the awkward ladders as I stayed in the tree and together we would split the crate money.

But being with a friend does lose you time – you tended to gab, fool around, have a smoke, take longer breaks. I made more cash alone.

If nights were clear, a bunch of us would take his Land Rover and other cars and storm through the black orchards chasing each other and having apple fights…clearly more fun than picking. We never got caught.

The orchard was run on the ground by a foreman called Jeff. He had a funny relationship with the warehouse boss. They talked, worked together but clearly kept space between them. Later I was told they not only had swapped spouses, but their kids too. The rural life, it’s another country.

The owner was Mr Fremont. We called him Mr because he was the boss of the whole operation. He was young and word had it he had Boston Money (never a compliment in Maine) who was just playing around with a new hobby of running an orchard. He let the managers operate the place and stayed in his beautiful farm house on the edge of a ridge with its swimming pool, his fancy four wheel drive pick ups, his easy city laughter.

In other seasons, there was other orchard work you could pick up. In May, you planted – each tree 17’ apart. That was on a day rate. In the late summer it was thinning – two out of three buds would go. And in winter, on snowshoes, there was pruning when the wood was sleeping and a cut was easy.

The work wasn’t that hard. Climbing trees for money. Because it was piecework, you could slack off if you had enough for the week. You could do the full ten hours if you needed cash. One time, I filled three crates. The Nova Scotians congratulated me even though they easily put away six crates each. It was that kind of job.

Do you know Robert Frost’s poem of the same name. It’s one of my favourites. I can say it by heart. And your essay is a confirmation for me that the poem is true.

Those Nova Scotians and their tricks. Good pic of Marshall too