Part 1: No more the world’s best governed city.

New Birmingham City Council leader John Clancy faces a daunting and unenviable task to avoid the danger of direct rule from Whitehall, reverse unprecedented civic decline and overcome the city’s low level (and still largely unflattering) national profile. A lack of foresight, poor political leadership, spurned opportunities and rank bad luck all helped the city reach this point but there were other markers along the way. All this week, Steve Beauchampé considers some key – and some more obscure – reasons why Birmingham might be in this mess.

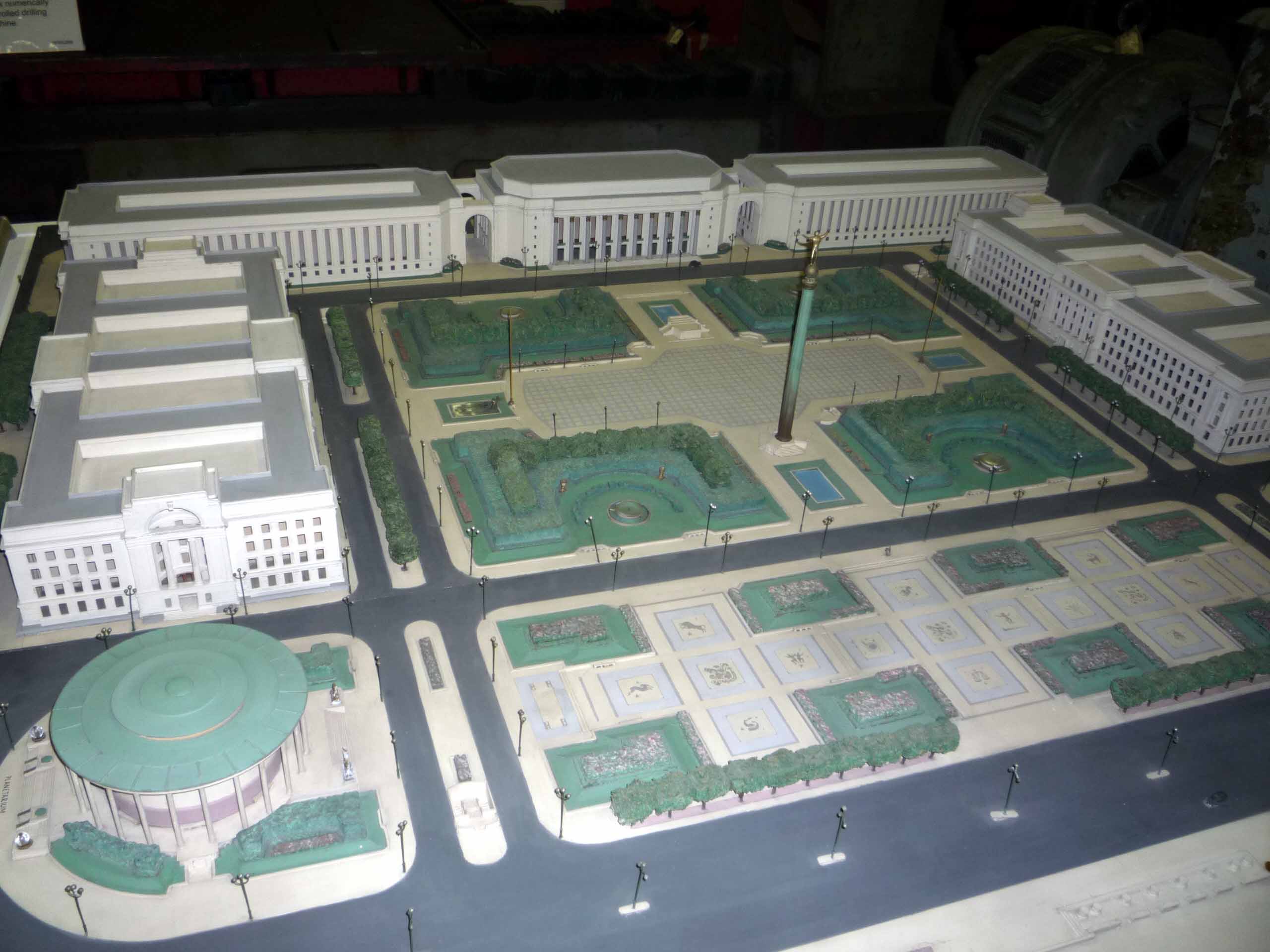

Had the Second World War not intervened, Birmingham could have had a neo-classical civic centre where today stands Centenary Square and the Library of Birmingham. Colossal in scale and ambition, the only element to be realised was Baskerville House but a scale model of the proposals in the Museum and Art Gallery shows that had the entire complex been built, and then survived Hitler’s bombs and Herbert Manzoni’s wrecking ball, it would now be Grade 1 listed and probably the most loved, photographed and iconic part of the city.

It was not to be but by the late 1990s the area roughly bounded by Victoria Square, Chamberlain Square, south and central Paradise Circus and Centenary Square made up Birmingham’s civic centre, where nearly all of its principal public buildings were located. The Council House, Museum and Art Gallery, Town Hall, Central Library, Library Theatre, Adrian Boult Hall, Birmingham Conservatoire, Baskerville House, the International Convention Centre and Symphony Hall, the Registry Office and Birmingham Repertory Theatre complex, along with the three aforementioned public squares were all here, whilst the National Indoor Arena was a mere few hundred yards away.

By 2015 the ICC, Symphony Hall and the NIA have all been sold (ditto the National Exhibition Centre), the Registry Office demolished, with the Adrian Boult Hall and Conservatoire soon to disappear along with the Central Library as part of a multi-decade re-build which will see a purely commercial development, with privately managed streets and squares, occupying what was formerly a swathe of public land. In theory the new Library of Birmingham development in Centenary Square should mitigate some of these effects but with areas of the building now rented to outside organisations, it too is feeling increasingly like a commercial enterprise.

Factor in the sale or closure of numerous other Council owned properties throughout the city, brought about in part by the seismic and often ideologically driven cuts in government funding that followed the financial and banking sector led recession of 2008 (such cuts estimated to be around £850 million between 2010-2017), but also by the obsession with outsourcing and privatisation of public services, and it becomes clear that the civic footprint however defined has shrunk alarmingly. As 2015 ends, the council’s reach and remit, its staffing levels and ability to provide traditional and necessary public services have been diminished as never before, with yet further cuts still to come.

The notion of outsourcing public services to the private sector and engaging consultants are constructs of the New Labour governments of 1997-2010 but outsourcing has been enthusiastically embraced and taken further by the Conservatives. The result, not only in Birmingham but throughout much of the UK, has been the drawing up of agreements and contracts considerably more favourable to the private sector, as local authorities, lacking expertise in such matters, found themselves outmanoeuvred and outwitted to the detriment of council tax payers, and tied into long-term deals that were decidedly not to the public’s advantage.

The situation has been particularly acute in Birmingham, most notably regarding the council’s Service Birmingham contract with Capita, the company at one point enjoying £58 million per annum profit from the deal, as well as a second contentious contract with Amey covering street repairs and maintenance.

It is in the nature of such agreements that key elements are routinely redacted, unable to be publicly disclosed under secretive ‘commercial confidentiality’ clauses. With transparency and accountability in retreat and local authorities strongly encouraged by Whitehall to devolve many of their remaining operations to third sector organisations or volunteers, whilst further depleting their property portfolios, and all under a culture of ‘light touch regulation’, the last thing needed was for the traditional local authority cross-party rôle of scrutiny, oversight and expertise to be downgraded or abolished.

But it was. The culprit was again the Blair government, the Local Government Act 2000 forcing local authorities to replace the long established committee system (which gave all parties committee seats proportional to their share of the popular vote) with a Leader and Cabinet. At a stroke this removed opposition councillors from the decision-making process, changing a generally consensual form of local governance into an adversarial one.

In Birmingham the expertise and sage minds of numerous councillors was squandered as the ruling party alone voted on policy whilst overview and scrutiny became reactive where it had previously been proactive. Furthermore the change placed additional powers of patronage in the hands of already emboldened council leaders.