Steve Beauchampé considers what’s behind Iain Duncan Smith’s resignation

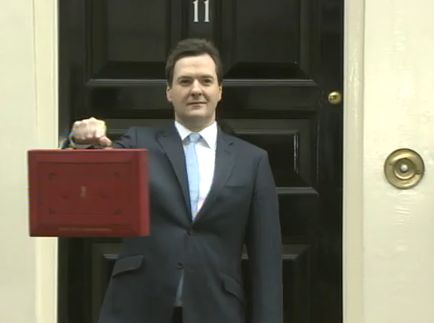

George Osborne, it is claimed, rather enjoys the comparison with Julius Caesar. The Chancellor of the Exchequer bears a certain physical resemblance to depictions of the Roman Emperor and a haircut in 2015 only increased the similarities. And, like Caesar, Osborne is desirous of the throne. Yet as a very bad week at the office for Osborne nears its end, it appears that like Caesar he may have been the victim of a clinical political assassination.

Knifed in the front rather than the back – and by a man whose cuts in financial support for the poor and the ill make the name Brutal more appropriate than Brutus – Osborne’s chances of succeeding David Cameron as Prime Minister look considerably diminished following the resignation (and just as importantly the resignation letter) of Work and Pensions Secretary Iain Duncan Smith and the outcry from his own party that greeted the Chancellor’s latest set of budgetary failings, miscalculations and missed targets.

Duncan Smith’s resignation was caused by a series of factors relating to the Treasury’s repeated demands on his Department to bear what he viewed as too large a proportion of Whitehall spending cuts, growing personal animosity between himself and George Osborne and the manner in which Duncan Smith’s welfare reforms have been repeatedly used by Osborne as a way of cementing his own political credentials. Frustration too, it would seem, from the Work and Pensions Secretary that his ongoing suggestions that pensioner benefits (such as the Winter Fuel Payment and free television license) should no longer be protected from spending reviews were ignored.

Yet the tipping point appears to have been that Osborne, supported as ever by Prime Minister David Cameron, brought forward the reductions to Personal Independence Payments that Duncan Smith had been working on for some time, and used them in his budget in a way that married them in public perception to tax cuts for the wealthier and wealthiest. Duncan Smith believed that his reforms should not only have been separated from such toxic fiscal measures, but in line with his mantra that it should always pay to work, they should follow – rather than precede – the implementation of the National Living Wage. Yet with the Government signalling that it would abandon the policy altogether, Duncan Smith faced the prospect one of his core benefit reforms being lost before he had even had chance to argue its merits.

The fissures between Duncan Smith and both Cameron and Osborne are wide and whilst they have recently been most visible over the EU referendum, they can be traced to Osborne’s rôle in the coup to replace Duncan Smith as Conservative Party Leader by Michael Howard in late 2003 (with Howard replaced by David Cameron just over two years later).

Thus Iain Duncan Smith’s resignation certainly allows him both more time and freedom to campaign for Britain to leave the EU, a result which would no doubt be all the more satisfying for him given that it would terminate the political careers of both Prime Minister and Chancellor, as well as possibly facilitating the erstwhile Work and Pensions Secretary a swift return to front line politics.

Yet even without the link to tax reductions that Osborne’s intervention allowed to ferment, Iain Duncan Smith may well have discovered that his plans to reduce PIP payments for the disabled would have courted widespread unpopularity. For it may be that not only are a significant number of the electorate becoming tired with Osborne’s perpetual austerity at a time when many economic indices are going south, but that voters have increasingly had it with the continual raids on the income of the disabled and the working poor, worse that they are overseen by millionaire Ministers such as David Cameron, George Osborne and Iain Duncan Smith.