Allowing local authorities to retain business rates only rights one of many wrongs imposed on them by central government writes Steve Beauchampé

Let us limit any praise for Chancellor George Osborne for finally, after five years of stalling, returning (if only partially) the collection of local business rates to local councils (yet another of his ‘theft policies’ – this one stolen from both Labour and the Liberal Democrats), something taken from them by the Thatcher government in the 1980s.

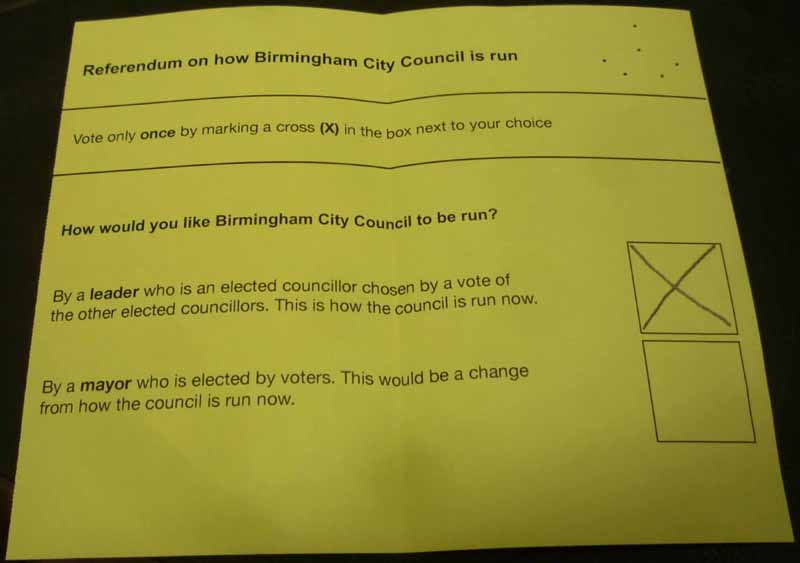

Because as with everything Osborne does, there is a subtext, or an unpalatable, deliberately disguised truth. And it is this… that the only regions that will be allowed to increase business rates at any point in the future (and by no more than 2% per annum) are those that agree to be run by a mayor, and only then is a rise permissible if it is approved by a majority of the businesses represented on the Local Enterprise Partnerships.

This sort of nonsense is typical. Local government in England is weighed down by Westminster’s rules and regulations designed to stymie or restrict its ability to govern and take decisions.

While Osborne may speak of regional devolution, albeit always under his terms and littered with restrictions and caveats (such as the imposition of Metro mayors despite recent referendums where the mayoral concept was firmly rejected, not least in Birmingham and Coventry), the reality is that the present government has spent over half a decade aggressively emasculating local authorities and rendering them increasingly powerless.

Witness the privatisation of vast swathes of public services (started by Blair and Brown but continued apace under Cameron and Osborne) and the forced sale of local authority land and property on an unprecedented scale.

Witness the rise of Academy Schools and the imposition of regulations on the state sector which make their widespread establishment almost a given, passing control of schooling to Whitehall and creating mini educational business empires in the process, a development exploited further by the Tories creation of the council funded, but far from publicly accountable, Free Schools programme.

Our core public services, including transport, housing, libraries, leisure centres, health and the legal and justice systems, are increasingly operated by huge private organisations such as Serco, Amey, Veolia, G4S and the Capita group, mostly headquartered in London and with strategic decision making remote from the people they are meant to serve.

It is a world in which accountability and scrutiny is at best arms length, if it exists at all, and with contracts heavily redacted or hidden from public gaze under the guise of commercial confidentiality, or locked behind complex Freedom of Information Act rules.

It is a world in which local government plays to markedly different rules than the private sector, a world in which public purse grant funding is denied to councils but is readily available when buildings and services are transferred to other forms of ownership, a world in which layers of beaurocracy are imposed on the public sector with the specific intention of encouraging and even forcing the transfer of services, power and responsibility from local government into the hands of the profit motivated private sector.

In Birmingham the situation is yet more critical. Whilst central government cuts to municipal budgets have hit hardest in Labour controlled metropolitan areas (and were designed so to do), the city is about to suffer from the consequences of the Kerslake Report.

Established by former Communities and Local Government Secretary Eric Pickles (a man whose antipathy to Labour councils was boundless), Lord Robert Kerslake (his ennoblement confirmed following the presentation of his report, though this might have been co-incidental) recommended both a reduction in the number of councillors serving Birmingham (from 120 to 100) and replacement of the present electoral system whereby a third of council seats are contested in three years out of four (with no elections in the fourth year), beginning in 2018.

Thus, at a time when Birmingham’s population is rising, the size of its wards (roughly 10,000 people) and thus the potential increased workload for each councillor, is increasing. By contrast, following the changes the number of residents per Ward in Coventry will be around half that of Birmingham.

Those local councillors that remain will also see their powers reduced, with their ability to influence and affect city-wide decisions all but removed. A democratic deficit of critical proportions concurrent with massive central government funding reductions and widespread staff cuts, all exacerbated by the single status equal pay ruling whereby around a billion pounds was owed to certain categories of current and former council employees.

Assailed on all sides, Birmingham, once a model for local government in the Victorian and Edwardian era, is struggling even to deliver basic services.

Meanwhile, the finances, powers and influence of business focused and non-elected Local Enterprise Partnerships are increasing and the lines of democratic accountability of the newly forming Combined Authorities and Metro Mayors are either far from clear in the case of the former, or very troubling in the case of the latter.

Open government, accountable government, democratic government? I think not.