The trick isn’t to give people what they want, but to give them what they don’t yet know that they want, says Steve Beauchampé.

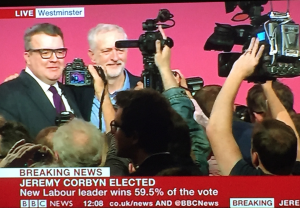

The consensus amongst political analysts is that Labour can’t win power under Jeremy Corbyn’s leadership. After misreading May’s General Election result and then writing off Corbyn’s chances of winning his party’s subsequent leadership contest – and even underestimating the size of his eventual victory – these ‘experts’ might yet be in for another surprise.

Four years and eight months (or 242 weeks) is a long time in politics and attempting to predict the electorate’s mood that far from the 2020 General Election is nigh impossible. For this reason alone a Corbyn-led Labour victory in 2020 should not be ruled out, but whilst the many arguments against such a scenario have been aired repeatedly, there are plenty in favour.

Importantly, for all the lazy, unsubstantiated claims that Corbyn’s politics are stuck in a 1970s/80s time warp, even a cursory analysis of his policy ideas indicates that most are highly relevant to contemporary Britain and more akin to those promoted by the social democratic parties found throughout much of western Europe…not least the rather popular SNP. His arguments resonate, not particularly with hard left socialists, but if turnout at his leadership election hustings is any indication, with a substantial cross-section of society; covering all ages, genders and ethnicities, and in all parts of the Queendom. A much wider demographic in fact than any other British political party or politician can lay claim to.

The Labour Party is not being taken over by a bunch of Scargillite 1980s throwbacks, but by hundreds of thousands of energised and passionate people, the Corbynieres, clamouring to be part of a politics that has finally given them hope and a vision that they can stand behind. Hope that a plausible alternative exists to the ideology that has created an ever-widening gap between rich and poor, reduced everything of value to the mere measure of its economic worth and systematically dismantled both the notion and actuality of public services, transferring them to the private sector who collectively make billions of pounds in profit from first paring them back and running what remains.

And hope that the stifling, cosy consensus at the heart of British political life for twenty years and more might be about to break, to snap apart as arguments shut out of the mainstream find place in a political discourse that is already changing from moribund to exhilarating, just as it has in Scotland. By altering the narrative of politics, by redefining the terms of the debate and showing long hidden or little explored possibilities, Jeremy Corbyn highlights the maxim that the trick isn’t giving people what they want, it’s giving them what they don’t yet know that they want.

Who knows how many will align themselves with this movement in the months ahead. But expect Labour Party membership to rise further; and with this rise the disconnection between many of the party’s senior figures and that new membership will become a chasm. And who knows how many of the 75% of those on the electoral register who rejected the Conservatives in May will be drawn in to this new Labour. Certainly, many of the 1.1 million that voted Green and 3.9 million that backed UKIP yet saw their cumulative votes rewarded with a mere two seats might switch allegiance to a party that at least has a chance of attaining power.

Then factor in Jeremy Corbyn’s not inconsiderable attributes of integrity, honesty and conviction. Unlike his adversaries across the floor of the Commons (and some of those behind him) Corbyn is not wealthy (just comfortable and living fairly parsimoniously) or well connected. Nor does he socialise with business leaders, senior figures in the financial and media sectors or cosy up to party donors. Jeremy Corbyn may work at Westminster, but he is decidedly not a creature of it. Attributes that form part of his appeal, but tell nothing like the whole story.

At 66 years old Jeremy Corbyn can remember Harold Macmillan being Prime Minister – and with such longevity comes wisdom and experience – around twenty years more than Cameron or Osborne, Theresa May or Boris Johnson could hope to have. Resolutely politically unspun, Corbyn eschews personal attacks whilst his manner is courteous, considered and unassuming, behaviour atypical of the braying, jeering, name calling mob mentality of British political life and parliament in particular. To his adversaries this will be disconcerting and to the general public it will be refreshing and attractive.

Corbyn’s approach to party differs too. Rejecting the top down imposition of policies that was a hallmark of New Labour alongside its attendant pseudo-Presidential style of governance, he encourages an open source politics where participation and debate amongst party members at all levels helps determine policies. And from amongst the 16,000 volunteers who ran his campaign or the thousands more drawn to the party by his inspiration, will emerge names that we do not yet know, with ideas that we have not yet heard, to flesh out the next manifesto and add depth to his team. Because this is not simply going to be just the Jeremy Corbyn show.

The Conservatives meanwhile should be careful what they wish for. Most are euphoric, but a few sage heads within the party have cautioned against seeing Corbyn’s victory as a free pass to a decade or more of electoral success. Crucially, by offering a coherent and plausible alternative to the ideology of Prime Minister David Cameron and Chancellor George Osborne and its attendant tacking to the right of what constitutes the political centre ground, Labour will throw the Conservative’s agenda into sharper definition, exposing it as a dogma of ultra-capitalism which forces a long hours, low wage economy on millions whilst viciously attacking the most vulnerable.

Suddenly, the Conservatives will find their policies dissected and opposed, relentlessly and articulately. A Labour Party headed by Liz Kendall or Yvette Cooper, by Chuka Umunna, Dan Jarvis or Tristram Hunt, chasing votes by merely offering a less extreme alternative to the Tories, could never achieve this.

By 2020 the Conservatives will have been in government for a decade, and after two five-year terms, as with many governments, the electorate might have had enough. The EU referendum may result in considerable internal upheaval for the party and, if Britain votes to leave, then the credibility and political careers of both Cameron and Osborne (currently favourite to succeed the Prime Minister) could be shot. The growing possibility of a second global recession, but this time happening on the Conservative’s watch, might be equally disastrous, especially for a government heavily dependent for its electability on the perception of its economic competence.

With a majority of just twelve, only a small dip in the Conservatives’ popularity could result in a hung parliament (although potential changes to parliamentary boundaries might bolster that majority). It’s difficult to know where the Tories might turn to should that happen; a deal with the Unionists in Northern Ireland, shored up by UKIP’s Douglas Carswell? Threadbare choices indeed. Labour however could assemble a coalition involving (some or all of) the Liberal Democrats under the auspices of social democrat leftie Tim Farron, the SNP, Plaid Cymru, the SDLP and the Greens.

If Jeremy Corbyn’s radical and so unexpected intervention can inspire and motivate those left-leaning voters and shift mainstream political discourse onto ground where it is all but a stranger, and all in the face of an intensely hostile media who will cut him no slack, then the impossible might again become possible.