By Alan Clawley.

Andy Munro’s article on 9 August was a useful reminder that there have been previous youth rebellions which the government of the day were eventually forced to react to; despite initially condemning them as purely criminal.

I was involved in the ‘regeneration game’ too, but I go back to 1974 when I came to Small Heath to work on the Birmingham Inner Area Study (BIAS) (the others were in Stockwell in London and Toxteth in Liverpool). Commissioned by the Department of the Environment the IAS followed the Home Office’s Community Development Programme (CDP) one of which was in Saltley in the early 1970s.

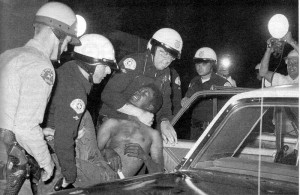

The impetus behind the setting up of the CDP was the government’s fear that the riots in the inner city district of Watts in Los Angeles in 1965 would spread to Britain’s deprived inner city communities. The idea was allowed to take root that there was a direct link between the run-down state of the environment, the lack of jobs, poor education, social problems and the high likelihood of riots. The left-leaning professionals who worked in the CDP came to some uncomfortable conclusions for their paymasters; their solution to the problems of inner city arrears such as Saltley – radical re-structuring of the capitalist economy – scared the government into adopting a more managerialist approach with the IAS that aimed to find better ways to co-ordinate services to benefit the residents of the inner city.

There have been may other programmes focussed on the inner city since, including the Handsworth Task Force, the Special Temporary Employment Programme (STEPS), the Community Programme, the City Challenge Bid, the Single Regeneration Budget, and the Neighbourhood Renewal Fund.

Over the years it was realised that it was too simplistic to focus just on the inner city as the only or main source of social unrest. Problems began to emerge in the new council estates that were built in the 70s to provide a better physical environment for those displaced by slum clearance in the inner cities. In the meantime the communities living in the inner cities learned to live with each other and their housing was much improved under the Urban Renewal programmes ending in the mid 80s.

Given the good community relations that have existed for a couple of decades in Birmingham’s inner cities it was regrettable that a TV reporter commenting on 10 August 2011 on the tragic death of the three men in Winson Green, referred to racial tensions ‘re-surfacing’. As Andy points out in his article, the Handsworth riot was not caused primarily by racial tension. The shops that were attacked and looted happened to be run by Asians, because most shops were being run by Asians. In Los Angeles in 1992 shops owned by Koreans were attacked in disturbances. The motivation of the rioters in these cases seems to have been sheer material envy and their targets just happened to be businesspeople of another race.

The riots of August 2011 are also, at first sight, about material envy; but the targets have shifted away from the inner cities to the big shopping centres – such as Croydon and Birmingham’s Bull Ring.

It may suit the broadcast media to perpetuate the myth that the inner cities are the seat of racial tensions. They love conflict and like to reinforce the stereotype of the inner city ghetto, but this is the laziest of journalism and nowhere near the truth.

If there is anything to learn from past troubles it’s that they are invariably inflamed by economic disadvantage and gross inequality rooted in discrimination of various kinds. The South Central area of Los Angeles known as Watts or Compton was the worst land in the city and the only place where the authorities allowed black people to settle in the 1920s. British society does not have the USA’s recent history of racial discrimination, but religious discrimination played a big part in fomenting the fairly recent Northern Ireland troubles.

Living in the inner city may not carry the stigma that it once did, but there are other ways in which some young people can be stigmatised and disadvantaged. In an increasingly competitive world, when material success is the only measure of a person’s worth, youngsters who know they have no prospect of achieving it are labelled as failures and called ‘scum’ by the already-successful. The visibility of wealthy role models such as Rio Ferdinand and Alan Sugar only make their failure all the more obvious.